Next: Multidimensional Integrals

Up: Lecture_14_web

Previous: Lecture_14_web

Next: Multidimensional Integrals

Up: Lecture_14_web

Previous: Lecture_14_web

Subsections

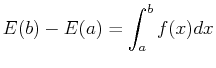

Consider the type of integral that everyone learns initially:

|

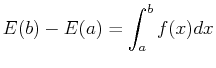

(14-1) |

The equation implies that  is integrable and

is integrable and

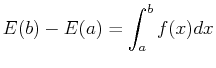

|

(14-2) |

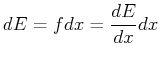

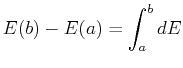

so that the integral can be written in the following way:

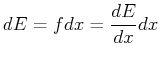

|

(14-3) |

where  and

and  represent ``points'' on some line

where

represent ``points'' on some line

where  is to be evaluated.

is to be evaluated.

Of course, there is no reason to restrict integration to a

straight line--the generalization is the integration

along a curve (or a path)

.

.

|

(14-4) |

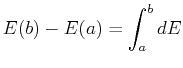

This last set of equations assumes that the gradient exists-i.e., there

is some function  that has the gradient

that has the gradient

.

.

If the function being integrated along a simply-connected

path (Eq. 14-4)

is a gradient of some scalar

potential, then the path between two integration points

does not need to be specified: the integral is independent of path.

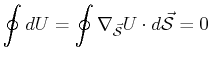

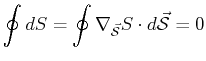

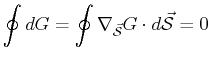

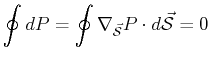

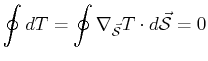

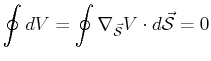

It also follows that for closed paths, the integral of the gradient

of a scalar potential is zero.1

A simply-connected path is one that does not self-intersect or can

be shrunk to a point without leaving its domain.

There are familiar examples from classical thermodynamics of simple

one-component fluids that

satisfy this property:

Where

is any other set of variables that sufficiently

describe the equilibrium state of the system (i.e,

is any other set of variables that sufficiently

describe the equilibrium state of the system (i.e,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  for

for  describing a simple one-component fluid).

describing a simple one-component fluid).

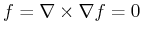

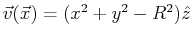

The relation

curl grad  provides method for testing whether some general

provides method for testing whether some general

is independent of path. If

is independent of path. If

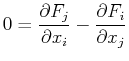

|

(14-7) |

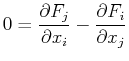

or equivalently,

|

(14-8) |

for all variable pairs  ,

,  ,

then

,

then

is independent of path.

These are the Maxwell relations of classical thermodynamics.

is independent of path.

These are the Maxwell relations of classical thermodynamics.

MATHEMATICA Example

Example |

| (notebook Lecture-14) |

| (html Lecture-14) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-14) |

| Path Dependence, Curl, and Curl=0 subspaces

This

example will show that the choice of path matters for

a vector-valued function that does not have vanishing curl

and that it doesn't matter when integrating a function with

vanishing curl.

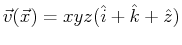

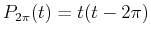

- Path-dependent/Non-conserving Field

- Verify that the function

does not have vanishing curl.

does not have vanishing curl.

- Integrate

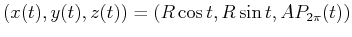

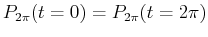

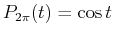

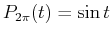

along a path that is wrapped around a cylinder of

radius

along a path that is wrapped around a cylinder of

radius  , (e.g.,

, (e.g.,

,

where

,

where

)

)

- Calculate the integral specifically for

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

.

.

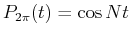

- Path-independent/Conservative Field

- Verify that, for the function

,

,

.

In fact,

.

In fact,

.

.

- Integrate

along the same cylindrical-type path as above

and see that the integral always vanishes--it is path-independent.

along the same cylindrical-type path as above

and see that the integral always vanishes--it is path-independent.

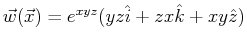

- Path independent on a Subspace

- The vector function

only vanishes on the cylinder or radius

only vanishes on the cylinder or radius  .

.

- It is easy to find

such that

such that

:

:

In fact, because we could add any vector function that has vanishing curl

to  there are an infinite number of

there are an infinite number of  such that

such that

.

.

- Therefore, if we integrate

along a path that is restricted to the

cylinder it should be path independent.

along a path that is restricted to the

cylinder it should be path independent.

- Using the same methods as above, we find that the integral on the cylinder will

be independent of

--the vector function

--the vector function  is independent of path

as long as the path remains on the cylinder.

is independent of path

as long as the path remains on the cylinder.

|

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![]() is integrable and

is integrable and

![]() .

.

![]() provides method for testing whether some general

provides method for testing whether some general

![]() is independent of path. If

is independent of path. If