Perhaps the most straightforward of the higher-dimensional integrations (e.g., vector function along a curve, vector function on a surface) is a scalar function over a domain such as, a rectangular block in two dimensions, or a block in three dimensions. In each case, the integration over a dimension is uncoupled from the others and the problem reduces to pedestrian integration along a coordinate axis.

Sometimes difficulty arises when the domain of integration is not so

easily described; in these cases, the limits of integration

become functions of another integration variable.

While specifying the limits of integration requires a bit

of attention, the only thing that makes these cases difficult is

that the integrals become tedious and lengthy.

MATHEMATICA![]() removes some of this burden.

removes some of this burden.

A short review of various ways in which a function's variable can appear in an integral follows:

|

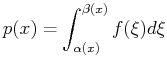

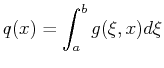

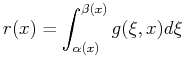

The Integral

|

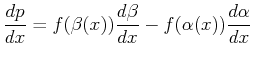

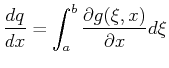

Its Derivative

|

|

|

Function

of limits |

|

|

|

Function

of integrand |

|

|

|

Function

of both |

|

|

| Extra Information and Notes

Potentially interesting but currently unnecessary |

||||||||

| Changing of variables is a topic in multivariable calculus that

often causes difficulty in classical thermodynamics.

This is an extract of my notes on thermodynamics: http://pruffle.mit.edu/3.00/ Alternative forms of differential relations can be derived by changing variables. To change variables, a useful scheme using Jacobians can be employed:

For example, the heat capacity at constant volume is:

Using the Maxwell relation,

which demonstrates that |

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-14) |

| (html Lecture-14) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-14) |

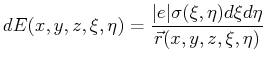

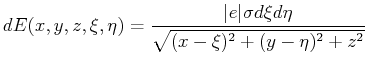

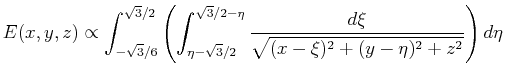

| Potential near a Charged and Shaped Surface Patch

Example calculation of the spatially-dependent energy of a unit point charge

in the vicinity of a charged planar region having the shape of an equilateral

triangle.

The energy of a point charge

for a patch with uniform charge,

For an equilateral triangle with sides of length one and center at the origin, the vertices can be located at

MATHEMATICA Integrate[1/r[x,y,z], {x,a,b}, {y,f[x],g[x]}, {z,p[x,y],q[x,y]}] would integrate over |