Next: Gradients and Directional Derivatives

Up: Lecture_12_web

Previous: Scalar Functions with Vector Argument

Next: Gradients and Directional Derivatives

Up: Lecture_12_web

Previous: Scalar Functions with Vector Argument

Subsections

There is no doubt that a great deal confusion arises from the

following question, ``What are the variables of my function?''

For example, suppose we have a three-dimensional space  ,

in which there is an embedded surface

,

in which there is an embedded surface

=

=

where

where

is a

vector that lies in the surface,

and an embedded curve

is a

vector that lies in the surface,

and an embedded curve

.

Furthermore, suppose there is a curve that lies within the surface

.

Furthermore, suppose there is a curve that lies within the surface

.

.

Suppose that

is a scalar function of

is a scalar function of

.

.

Here are some questions that arise in different applications:

- How does

vary as a function of position?

vary as a function of position?

- How does

vary along the surface?

vary along the surface?

- How does

vary along the curve?

vary along the curve?

- How does

vary along the curve embedded in the surface?

vary along the curve embedded in the surface?

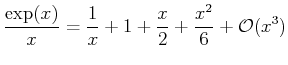

Taylor Series

The behavior of a function near a point is something that arises frequently

in physical models.

When the function has lower-order continuous partial derivatives (generally,

a ``smooth'' function near the point in question), the stock method to

model local behavior is Taylor's series expansions around a fixed point.

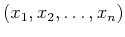

Taylor's expansion for a scalar function of  variables,

variables,

which has continuous first and second partial

derivatives near the point

which has continuous first and second partial

derivatives near the point

is:

is:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}& f(\xi_1 , \xi_2 , \ldots , \xi_n) = f(x_1 , x_...

...] +\ldots + \mathcal{O}\left[(\xi_n - x_n)^3\right] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img54.png) |

(12-8) |

or in a vector shorthand:

![$\displaystyle f(\vec{x}) = f(\vec{\xi}) + \left.\nabla_{\vec{x}} f\right\vert _...

...dot (\vec{xi} - \vec{x}) +\mathcal{O}\left[\norm {\vec{\xi} - \vec{x}}^3\right]$](img55.png) |

(12-9) |

MATHEMATICA Example

Example |

| (notebook Lecture-12) |

| (html Lecture-12) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-12) |

Approximating Surfaces

Example of turning a function of two variables,  into

an approximating function of four variables:

into

an approximating function of four variables:

- Start with a function

and expand it about a point

and expand it about a point

to second order--use

MATHEMATICA

to second order--use

MATHEMATICA 's Normal function to convert from

series representation to a parabolic representation.

's Normal function to convert from

series representation to a parabolic representation.

- The expansion is now a function of four variables--the first two variables

are the point the function is expanded around, and the second two are the

variable of the parabolic approximation at that point:

where

or

where

- Plot the function

for

for

and

and

for a selected number of points

for a selected number of points  .

.

|

Just a few of many examples of instances where Taylor's expansions are used are:

- linearization

- Examining the behavior of a model near a point

where the model is understood.

Even if the model is wildly non-linear, a useful approximation is

to make it linear by evaluating near a fixed point.

- approximation

- If a model has a complicated representation in terms

of unfamiliar functions, a Taylor expansion can be used to characterize

the `local' model in terms of a simple polynomials.

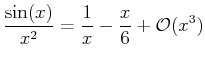

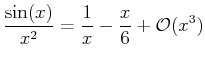

- asymptotics

- Even when a system has singular behavior (e.g, the

value of a function becomes infinite as some variable approaches a

particular value), how the system becomes singular is very important.

At singular points, the Taylor expansion will have leading order terms that are

singular, for example near

,

,

|

(12-10) |

The singularity can be subtracted off and it can be said that this

function approaches  "linearly" from below with slope -1/6.

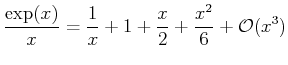

Comparing this to the behavior of another function that is singular

near zero:

"linearly" from below with slope -1/6.

Comparing this to the behavior of another function that is singular

near zero:

|

(12-11) |

shows that the  behavior is ``more singular.''

behavior is ``more singular.''

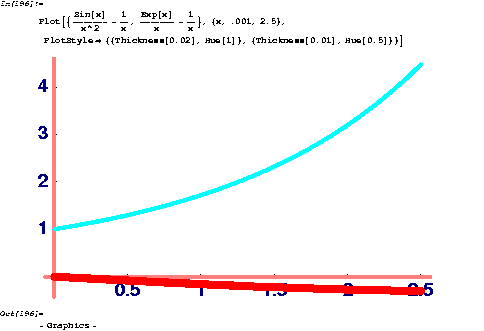

Figure 12-1:

Behavior of two singular functions near their

singular points.

|

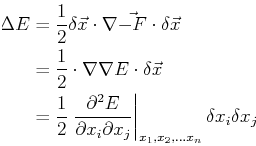

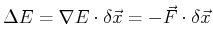

- stability

- In the expansion of energy about a point

is obtained, then the various orders of expansion can be interpreted:

- zero-order

- The zeroth-order term in a local expansion is

the energy of the system at the point evaluated.

Unless this term is to be compared to another point, it

has no particular meaning (if it is not infinite) as

energy is always arbitrarily defined up to a constant.

- first-order

- The first-order is related to the driving force

to change the state of the system. Consider:

|

(12-12) |

If force exists, the system can decrease it energy linearly by picking

a particular change

that is anti-parallel to the

force.

that is anti-parallel to the

force.

For a system to be stable, it is a necessary first condition that

the forces (or first order expansion coefficients) vanish.

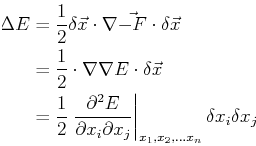

- second order

- If a system has no forces on it (therefore

satisfying the necessary condition of stability), then where

the system is stable or unstable depends on whether a

small

can be found that deceases the energy:

can be found that deceases the energy:

|

(12-13) |

where the summation convention is used above and the point

is one for which

is one for which  is zero.

is zero.

- numerics

- Derivatives are often obtained numerically in

numerical simulations.

The Taylor expansion provides a formula to approximate numerical

derivatives--and provides an estimate of the numerical error

as a function of quantities like numerical mesh size.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![]() ,

in which there is an embedded surface

,

in which there is an embedded surface

![]()

![]() =

=

![]() where

where

![]() is a

vector that lies in the surface,

and an embedded curve

is a

vector that lies in the surface,

and an embedded curve

![]() .

Furthermore, suppose there is a curve that lies within the surface

.

Furthermore, suppose there is a curve that lies within the surface

![]() .

.

![]() is a scalar function of

is a scalar function of

![]() .

.

![]() variables,

variables,

![]() which has continuous first and second partial

derivatives near the point

which has continuous first and second partial

derivatives near the point

![]() is:

is:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}& f(\xi_1 , \xi_2 , \ldots , \xi_n) = f(x_1 , x_...

...] +\ldots + \mathcal{O}\left[(\xi_n - x_n)^3\right] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img54.png)

![$\displaystyle f(\vec{x}) = f(\vec{\xi}) + \left.\nabla_{\vec{x}} f\right\vert _...

...dot (\vec{xi} - \vec{x}) +\mathcal{O}\left[\norm {\vec{\xi} - \vec{x}}^3\right]$](img55.png)