Next: Index

Up: Lecture_22_web

Previous: Differential Operators

Next: Index

Up: Lecture_22_web

Previous: Differential Operators

Subsections

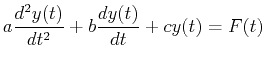

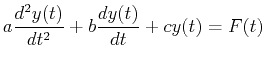

Methods for finding general solution to the linear inhomogeneous

second-order ODE

|

(22-21) |

have been developed and worked out in

MATHEMATICA examples.

examples.

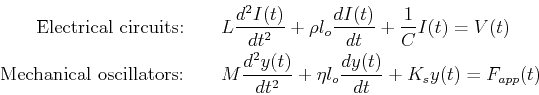

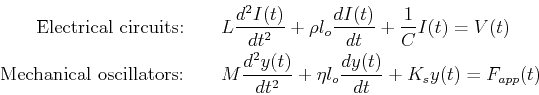

Eq. 22-21 arises frequently in physical models,

among the most common are:

|

(22-22) |

where:

| |

Mechanical |

Electrical |

Second

Order |

Mass  :

Physical measure of the ratio of

momentum field to velocity

:

Physical measure of the ratio of

momentum field to velocity |

Inductance  :

Physical measure of the ratio of stored

magnetic field to current

:

Physical measure of the ratio of stored

magnetic field to current |

First

Order |

Drag Coefficient

( is viscosity

is viscosity

is a unit displacement):

Physical measure of the ratio environmental resisting

forces to velocity--or proportionality constant

for energy dissipation with square of velocity

is a unit displacement):

Physical measure of the ratio environmental resisting

forces to velocity--or proportionality constant

for energy dissipation with square of velocity |

Resistance

( is resistance per unit

material length

is resistance per unit

material length

is a unit length):

Physical measure of the ratio of voltage drop

to current--or proportionality constant for power

dissipated with square of the current.

is a unit length):

Physical measure of the ratio of voltage drop

to current--or proportionality constant for power

dissipated with square of the current. |

Zeroth

Order |

Spring Constant  :

Physical measure of the ratio environmental force

developed to displacement--or proportionality constant

for energy stored with square of displacement

:

Physical measure of the ratio environmental force

developed to displacement--or proportionality constant

for energy stored with square of displacement |

Inverse Capacitance  :

Physical measure of the ratio of voltage storage rate

to current--or proportionality constant for energy storage rate

dissipated with square of the current.

:

Physical measure of the ratio of voltage storage rate

to current--or proportionality constant for energy storage rate

dissipated with square of the current. |

Forcing

Term |

Applied Voltage  :

Voltage applied to circuit as a function of time.

:

Voltage applied to circuit as a function of time. |

Applied Force  :

Force applied to oscillator as a function of time.

:

Force applied to oscillator as a function of time. |

For the homogeneous equations (i.e. no applied forces

or voltages) the solutions for physically allowable values

of the

coefficients can either be oscillatory, oscillatory

with damped amplitudes, or, completely damped with no oscillations.

(See Figure ![[*]](crossref.png) ).

The homogeneous equations are sometimes called autonomous

equations--or autonomous systems.

).

The homogeneous equations are sometimes called autonomous

equations--or autonomous systems.

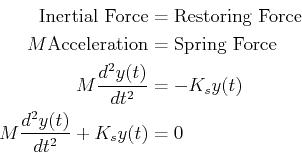

The simplest version of a homogeneous

Eq. 22-21 with no damping coefficient ( ,

,  , or

, or  )

appears in a remarkably wide variety of physical models.

This simplest physical model is a simple harmonic oscillator--composed

of a mass accelerating with a linear spring restoring force:

)

appears in a remarkably wide variety of physical models.

This simplest physical model is a simple harmonic oscillator--composed

of a mass accelerating with a linear spring restoring force:

|

(22-23) |

Here  is the displacement from the equilibrium position-i.e., the

position where the force,

is the displacement from the equilibrium position-i.e., the

position where the force,

.

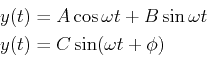

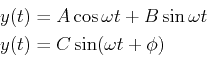

Eq. 22-23 has solutions that oscillate in time with frequency

.

Eq. 22-23 has solutions that oscillate in time with frequency  :

:

|

(22-24) |

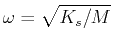

where

is the natural frequency of oscillation,

is the natural frequency of oscillation,

and

and  are integration constants written as amplitudes; or,

are integration constants written as amplitudes; or,  and

and  are integration constants written as an amplitude and a phase shift.

are integration constants written as an amplitude and a phase shift.

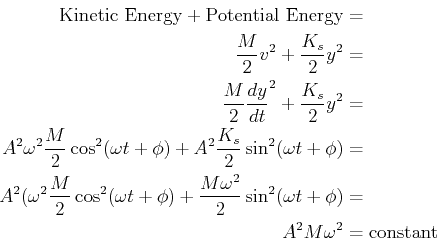

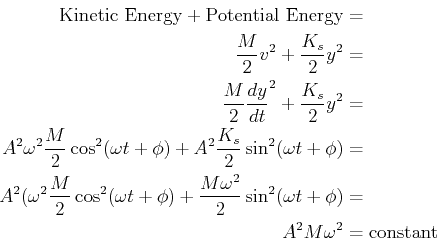

The simple harmonic oscillator has an invariant, for the

case of mass-spring system the invariant is the total energy:

|

(22-25) |

There are a remarkable number of physical systems that can be reduced to

a simple harmonic oscillator (i.e., the model can be reduced to

Eq. 22-23).

Each such system has an analog to a mass, to a spring constant, and thus

to a natural frequency.

Furthermore, every such system will have an invariant that is an analog

to the total energy--an in many cases

the invariant will, in fact, be the total energy.

The advantage of reducing a physical model to a harmonic oscillator is

that all of the physics follows from the simple harmonic oscillator.

Here are a few examples of systems that can be reduced to simple harmonic

oscillators:

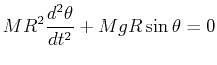

- Pendulum

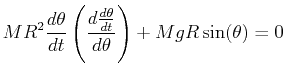

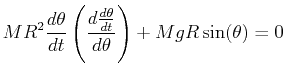

- By equating the rate of change of angular momentum equal to the

torque, the equation for pendulum motion can be derived:

|

(22-26) |

for small-amplitude pendulum oscillations,

,

the equation is the same as a simple harmonic oscillator.

,

the equation is the same as a simple harmonic oscillator.

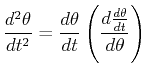

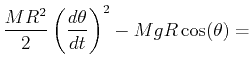

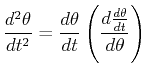

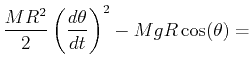

It is instructive to consider the invariant for the non-linear equation.

Because

|

(22-27) |

Eq. 22-26 can be written as:

|

(22-28) |

![$\displaystyle \ensuremath{\frac{d{}}{d{\theta}}}\left[\frac{M R^2}{2} \left( \ensuremath{\frac{d{\theta}}{d{t}}} \right)^2 - Mg R \cos(\theta)\right] = 0$](img106.png) |

(22-29) |

which can be integrated with respect to  :

:

constant constant |

(22-30) |

This equation will be used as a level-set equation to visualize pendulum

motion.

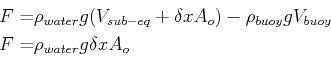

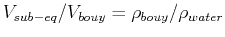

- Buoyant Object

- Consider a buoyant object that is slightly displaced from its

equilibrium floating position.

The force (downwards) due to gravity of the buoy is

The force (upwards) according to Archimedes is

The force (upwards) according to Archimedes is

where

where  is the volume of the buoy that is submerged.

The equilibrium position must satisfy

is the volume of the buoy that is submerged.

The equilibrium position must satisfy

.

.

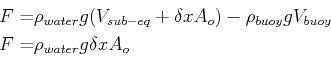

If the buoy is slightly perturbed at equilibrium by an amount  the force is:

the force is:

|

(22-31) |

where  is the cross-sectional area at the equilibrium position.

Newton's equation of motion for the buoy is:

is the cross-sectional area at the equilibrium position.

Newton's equation of motion for the buoy is:

|

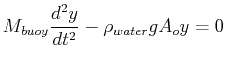

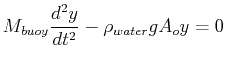

(22-32) |

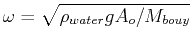

so the characteristic frequency of the buoy is

.

.

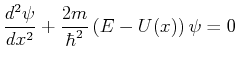

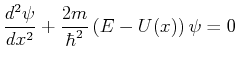

- Single Electron Wave-function

- The one-dimensional Schrödinger equation is:

|

(22-33) |

where  is the potential energy at a position

is the potential energy at a position  .

If

.

If

is constant as in a free electron in a box, then

the one-dimensional wave equation reduces to a simple

harmonic oscillator.

is constant as in a free electron in a box, then

the one-dimensional wave equation reduces to a simple

harmonic oscillator.

In summation, just about any system that oscillates about

an equilibrium state can be reduced to a harmonic oscillator.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![[*]](crossref.png) ).

The homogeneous equations are sometimes called autonomous

equations--or autonomous systems.

).

The homogeneous equations are sometimes called autonomous

equations--or autonomous systems.

![]() ,

, ![]() , or

, or ![]() )

appears in a remarkably wide variety of physical models.

This simplest physical model is a simple harmonic oscillator--composed

of a mass accelerating with a linear spring restoring force:

)

appears in a remarkably wide variety of physical models.

This simplest physical model is a simple harmonic oscillator--composed

of a mass accelerating with a linear spring restoring force:

![$\displaystyle \ensuremath{\frac{d{}}{d{\theta}}}\left[\frac{M R^2}{2} \left( \ensuremath{\frac{d{\theta}}{d{t}}} \right)^2 - Mg R \cos(\theta)\right] = 0$](img106.png)

constant

constant![]() the force is:

the force is: