Next: Harmonic Oscillators

Up: Lecture_22_web

Previous: Lecture_22_web

Next: Harmonic Oscillators

Up: Lecture_22_web

Previous: Lecture_22_web

Subsections

The idea of a function as ``something'' that takes a value

(real, complex, vector, etc.) as ``input'' and returns ``something else''

as ``output'' should be very familiar and useful.

This idea can be generalized to operators

that take a function as an argument and return

another function.

The derivative operator operates on a function

and returns another function that describes how

the function changes:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{D}[f(x)] & = \ensuremath{\frac{d{f}}{d{...

...)]\\ \mathcal{D}[f(x) + g(x)] = & D[f(x)] + D[g(x)] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img1.png) |

(22-1) |

The last two equations above indicate

that the ``differential operator'' is a linear operator.

The integration operator is the right-inverse of

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{D} [\mathcal{I}[ f(x)]] = \mathcal{D}[ \int f(x) dx]$](img3.png) |

(22-2) |

but is only the left-inverse up to an arbitrary constant.

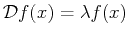

Consider the differential operator that returns a constant

multiplied by itself

|

(22-3) |

which is another way to write the

the homogenous linear first-order ODE and

has the same form as an eigenvalue equation.

In fact,

, can be

considered an eigenfunction of

Eq. 22-3.

, can be

considered an eigenfunction of

Eq. 22-3.

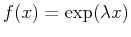

For the homogeneous second-order equation,

![$\displaystyle \left(\mathcal{D}^2 + \beta \mathcal{D} - \gamma \right)[ f(x)] = 0$](img6.png) |

(22-4) |

It was determined that there were two eigensolutions that can

be used to span the entire solution space:

|

(22-5) |

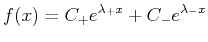

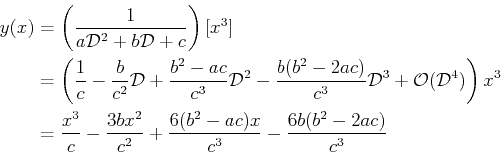

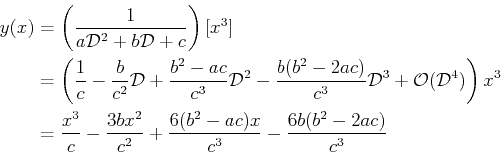

Operators can be used algebraically,

consider the inhomogeneous second-order ODE

![$\displaystyle \left(a \mathcal{D}^2 + b \mathcal{D} + c\right)[y(x)] = x^3$](img8.png) |

(22-6) |

By treating the operator as an algebraic quantity, a

solution can be found1

|

(22-7) |

which solves Eq. 22-6.

The Fourier transform is also a linear operator:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{F}[f(x)] =& g(k) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi...

...i}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(k) e^{-\imath k x} dk \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img10.png) |

(22-8) |

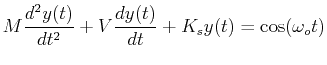

Combining operators is another useful way to solve differential equations.

Consider the Fourier transform,

, operating on the

differential operator,

, operating on the

differential operator,

:

:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{F}[\mathcal{D}[f]] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \ensuremath{\frac{d{f(x)}}{d{x}}} e^{i k x} dx$](img13.png) |

(22-9) |

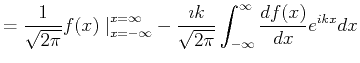

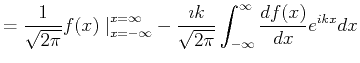

Integrating by parts,

|

(22-10) |

If the Fourier transform of  exists, then typically2

exists, then typically2

.

In this case,

.

In this case,

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{F}[\mathcal{D}[f]] = -i k \mathcal{F}[f(x)]$](img19.png) |

(22-11) |

and by extrapolation:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{F}[\mathcal{D}^2[f]] & = -k^2 \mathcal{...

...{D}^n[f]] & = (-1)^n \imath^n k^n \mathcal{F}[f(x)] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img20.png) |

(22-12) |

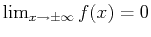

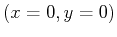

Consider the heterogeneous second-order linear ODE which

represent a forced, damped, harmonic oscillator that

will be discussed later in this lecture.

|

(22-13) |

Apply a Fourier transform (mapping from the time ( ) domain to

a frequency (

) domain to

a frequency ( ) domain) to both sides of 22-13:

) domain) to both sides of 22-13:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{F}[M \ensuremath{\frac{d^2{y(t)}}{d{t}^...

...ta(\omega-\omega_o) +\delta(\omega+\omega_o)\right] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img24.png) |

(22-14) |

because the Dirac Delta functions result from taking the

Fourier transform of

.

.

Equation 22-14 can be solved for the Fourier

transform:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{F}[y] = \sqrt{\frac{-\pi}{2}} \frac{ \left[ \delta(\omeg...

...ega_o) +\delta(\omega+\omega_o)\right] } { M \omega^2 + \imath \omega V - K_s }$](img26.png) |

(22-15) |

In other words, the particular solution Eq. 22-13

can be obtained by finding the

function  that has a Fourier transform equal the

the right-hand-side of Eq. 22-15-or, equivalently,

operating with the inverse Fourier transform on the

right-hand-side of Eq. 22-15.

that has a Fourier transform equal the

the right-hand-side of Eq. 22-15-or, equivalently,

operating with the inverse Fourier transform on the

right-hand-side of Eq. 22-15.

MATHEMATICA Example

Example |

| (notebook Lecture-22) |

| (html Lecture-22) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-22) |

| Operator Calculus and the Solution to the Damped-Forces Harmonic

Oscillator Model

MATHEMATICA does have built-in functions to take Fourier (and other kinds of)

integral transforms.

However, as will be seen below, using operational calculus to

solve ODEs is not necessarily simple in

MATHEMATICA

does have built-in functions to take Fourier (and other kinds of)

integral transforms.

However, as will be seen below, using operational calculus to

solve ODEs is not necessarily simple in

MATHEMATICA .

Nevertheless, it may be instructive to force it--if only as an

an example of using the good tool for the wrong purpose.

.

Nevertheless, it may be instructive to force it--if only as an

an example of using the good tool for the wrong purpose.

|

Operators to Functionals

Equally powerful is the concept of a functional which

takes a function as an argument and returns a value.

For example

![$ \mathcal{S}[y(x)]$](img31.png) , defined below, operates on

a function

, defined below, operates on

a function  and returns its surface of revolution's area

for

and returns its surface of revolution's area

for  :

:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{S}[y(x)] = 2 \pi \int_0^L y \sqrt{1 + \left(\ensuremath{\frac{d{y}}{d{x}}}\right)^2} dx$](img34.png) |

(22-16) |

This is the functional to be minimized for the question, ``Of all

surfaces of revolution that span from  to

to  ,

which is the

,

which is the  that has the smallest surface area?''

that has the smallest surface area?''

This idea of finding ``which function maximizes or minimizes something''

can be very powerful and practical.

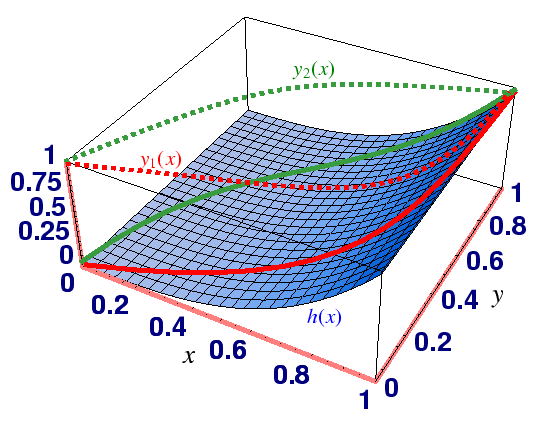

Suppose you are asked to run an ``up-hill'' race from some starting

point  to some ending point

to some ending point  and there

is a ridge

and there

is a ridge

.

What is the most efficient running route

.

What is the most efficient running route  ?3

?3

Figure:

The terrain separating the

starting point

and ending point

and ending point

.

Assuming a model for how much running speed slows with the

steepness of the path--which route would be quicker, one (

.

Assuming a model for how much running speed slows with the

steepness of the path--which route would be quicker, one ( )

that starts going up-hill at first or another (

)

that starts going up-hill at first or another ( ) that initially

traverses a lot of ground quickly?

) that initially

traverses a lot of ground quickly?

|

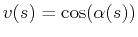

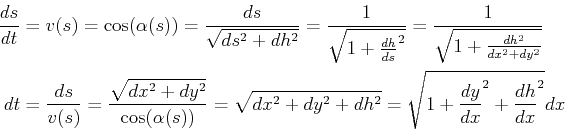

A reasonable model for running speed as a function of climbing-angle  is

is

|

(22-17) |

where  is the arclength along the path.

The maximum speed occurs on flat ground

is the arclength along the path.

The maximum speed occurs on flat ground  and running

speed monotonically falls to zero as

and running

speed monotonically falls to zero as

.

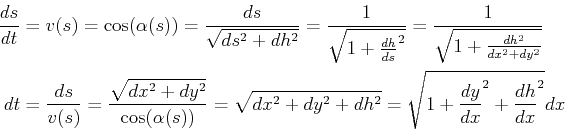

To calculate the time required to traverse any path

.

To calculate the time required to traverse any path  with endpoints

with endpoints

and

and  ,

,

|

(22-18) |

So, with the hill  , the time as a functional of the

path is:

, the time as a functional of the

path is:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{T}[y(x)] = \int_0^1 \sqrt{1 + {\ensuremath{\frac{d{y}}{d{x}}}}^2 + 4 x^2} \; dx$](img61.png) |

(22-19) |

There is a powerful and beautiful mathematical method for

finding the extremal functions of functionals which is

called Calculus of Variations.

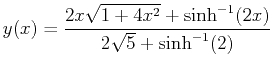

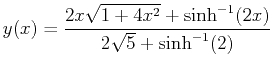

By using the calculus of variations, the optimal path  for

Eq. 22-19 can be determined:

for

Eq. 22-19 can be determined:

|

(22-20) |

The approximation determined in the

MATHEMATICA example above is

pretty good.

example above is

pretty good.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{D}[f(x)] & = \ensuremath{\frac{d{f}}{d{...

...)]\\ \mathcal{D}[f(x) + g(x)] = & D[f(x)] + D[g(x)] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img1.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{D}[f(x)] & = \ensuremath{\frac{d{f}}{d{...

...)]\\ \mathcal{D}[f(x) + g(x)] = & D[f(x)] + D[g(x)] \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img1.png)

![]()

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{D} [\mathcal{I}[ f(x)]] = \mathcal{D}[ \int f(x) dx]$](img3.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{split}\mathcal{F}[f(x)] =& g(k) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi...

...i}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(k) e^{-\imath k x} dk \end{split}\end{displaymath}](img10.png)

![]() , operating on the

differential operator,

, operating on the

differential operator,

![]() :

:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{F}[\mathcal{D}[f]] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \ensuremath{\frac{d{f(x)}}{d{x}}} e^{i k x} dx$](img13.png)

![]() , defined below, operates on

a function

, defined below, operates on

a function ![]() and returns its surface of revolution's area

for

and returns its surface of revolution's area

for ![]() :

:

![$\displaystyle \mathcal{S}[y(x)] = 2 \pi \int_0^L y \sqrt{1 + \left(\ensuremath{\frac{d{y}}{d{x}}}\right)^2} dx$](img34.png)

![]() to some ending point

to some ending point ![]() and there

is a ridge

and there

is a ridge

![]() .

What is the most efficient running route

.

What is the most efficient running route ![]() ?3

?3

![]() is

is

![]() for

Eq. 22-19 can be determined:

for

Eq. 22-19 can be determined:

![]() example above is

pretty good.

example above is

pretty good.