For first-order ordinary differential equations (ODEs),

![]() ,

one value

,

one value ![]() was needed to specify a particular solution.

For second-order equations, two independent values are needed.

This is illustrated in the following forward-differencing example.

was needed to specify a particular solution.

For second-order equations, two independent values are needed.

This is illustrated in the following forward-differencing example.

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-21) |

| (html Lecture-21) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-21) |

| A Second-Order Forward Differencing Example

Recall the example in Lecture 19 of a first-order differencing scheme: at each iteration the function grew proportionally to its current size. In the limit of very small forward differences, the scheme converged to exponential growth. Now consider a situation in which function's current rate of growth increases proportionally to two terms: its current rate of growth and its size.

Change in Value's Rate of Change

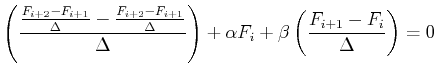

To Calculate a forward differencing scheme for this case, let

and then solve for the ``next increment''

|

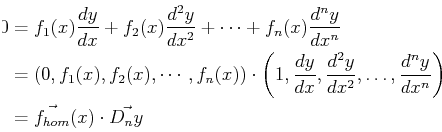

Therefore, a linear heterogeneous ordinary differential equation

can be written as a product of general functions of the

dependent variable and the derivatives for the ![]() -order linear

case:

-order linear

case:

|

(21-2) |

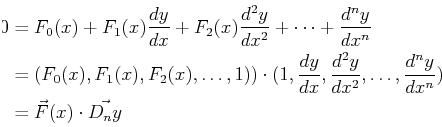

Equation 21-1 can always be multiplied by

![]() to generate the general form:

to generate the general form:

|

(21-3) |

For the second-order linear ODE, the heterogeneous form can always be written as:

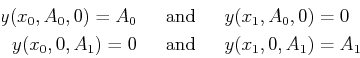

Because two values must be specified for each solution to a second order equation--the solution can be broken into two basic parts, each deriving from a different constant. These two independent solutions form a basis pair for any other solution to the homogeneous second-order linear ODE that derives from any other pair of specified values.

The idea is the following:

suppose the solution to Eq. 21-5

is found the particular case of specified parameters

![]() and

and

![]() , the solution

, the solution

![]() can be written

as the sum of solutions to two other problems.

can be written

as the sum of solutions to two other problems.

| (21-6) |

|

(21-7) |

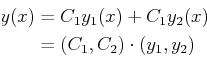

The two arbitrary integration constants can be included in the definition of the general solution:

|

(21-8) |