Next: Stokes' Theorem

Up: Lecture_16_web

Previous: Higher-dimensional Integrals

Next: Stokes' Theorem

Up: Lecture_16_web

Previous: Higher-dimensional Integrals

Suppose there is ``stuff'' flowing from place to place in three

dimensions.

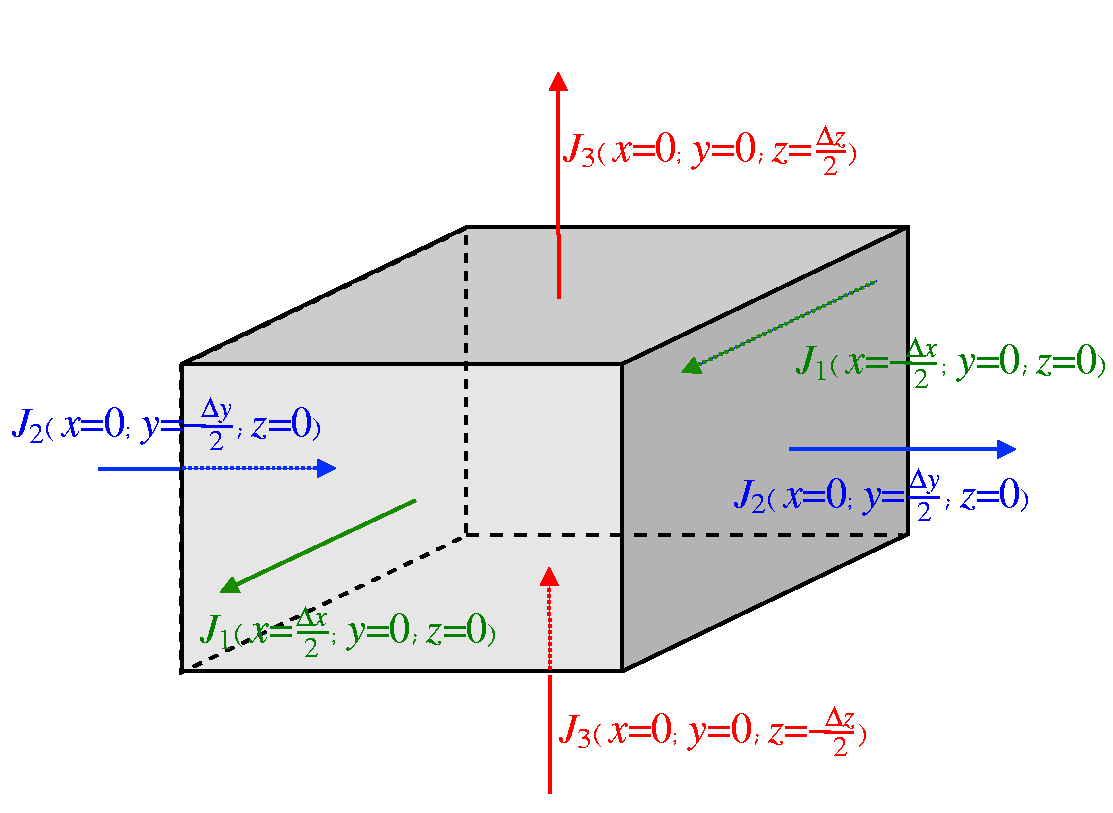

Figure:

Illustration of a vector ``flow field''  near

a point in three dimensional space.

If each vector represents the rate of ``stuff'' flowing per unit area

of a plane that is normal to the direction of flow, then the

dot product of the flow field integrated over a planar oriented area

near

a point in three dimensional space.

If each vector represents the rate of ``stuff'' flowing per unit area

of a plane that is normal to the direction of flow, then the

dot product of the flow field integrated over a planar oriented area  is the rate of ``stuff'' flowing through that plane.

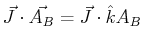

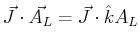

For example, consider the two areas indicated with purple (or dashed) lines.

The rate of ``stuff'' flowing through those regions is

is the rate of ``stuff'' flowing through that plane.

For example, consider the two areas indicated with purple (or dashed) lines.

The rate of ``stuff'' flowing through those regions is

and

and

.

.

|

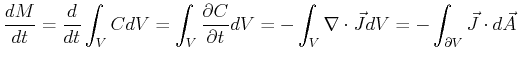

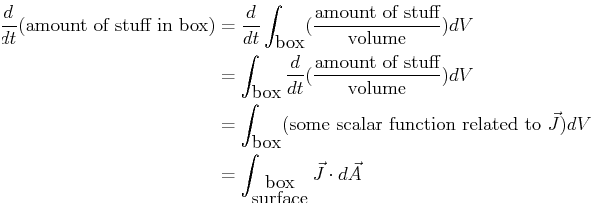

If there are no sources or sinks that create or destroy stuff

inside a small box surrounding a point, then the change in the

amount of stuff in the

volume of the box must be related to some integral over the box's surface:

|

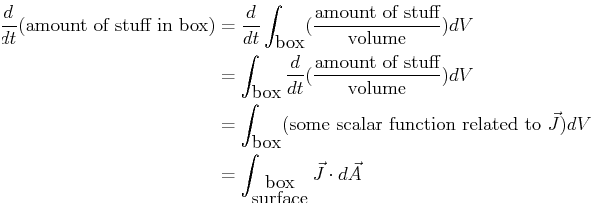

(16-1) |

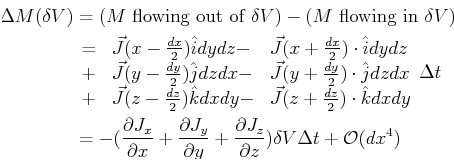

Figure 16-4:

Integration of a vector function near

a point and its relation to the change in that vector function.

The rate of change of stuff is the integral of flux over the

outside--and

in the limit as the box size goes to zero, the rate of change of

the amount of stuff is related to the sum of derivatives of the

flux components at that point.

|

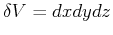

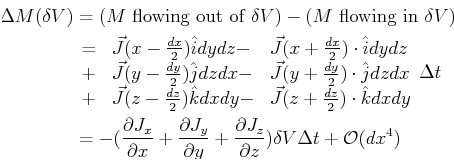

To relate the rate at which ``stuff  '' is flowing into a small

box of volume

'' is flowing into a small

box of volume

located at

located at  due to

a flux

due to

a flux  ,

note that the amount that

,

note that the amount that  changes in a time

changes in a time  is:

is:

|

(16-2) |

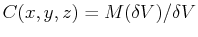

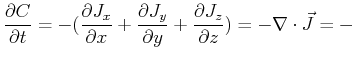

If

is the concentration (i.e., stuff per volume) at

is the concentration (i.e., stuff per volume) at  , then

in the limit of small volumes and short times:

, then

in the limit of small volumes and short times:

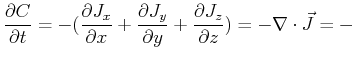

div div |

(16-3) |

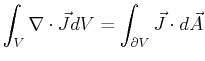

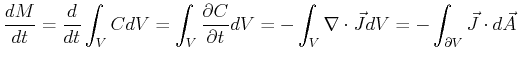

For an arbitrary closed volume  bounded by an oriented surface

bounded by an oriented surface

:

:

|

(16-4) |

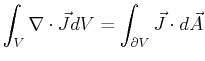

The last equality

|

(16-5) |

is called the Gauss or the divergence theorem.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![]() '' is flowing into a small

box of volume

'' is flowing into a small

box of volume

![]() located at

located at ![]() due to

a flux

due to

a flux ![]() ,

note that the amount that

,

note that the amount that ![]() changes in a time

changes in a time ![]() is:

is:

div

div