|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-15) |

| (html Lecture-15) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-15) |

| Representations of Surfaces

|

However, there are different ways to formulate representations of surfaces:

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-15) |

| (html Lecture-15) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-15) |

| Representations of Surfaces

|

Surfaces and interfaces play fundamental roles in materials science and engineering. Unfortunately, the mathematics of surfaces and interfaces frequently presents a hurdle to materials scientists and engineering. The concepts in surface analysis can be mastered with a little effort, but there is no escaping the fact that the algebra is tedious and the resulting equations are onerous. Symbolic algebra and numerical analysis of surface alleviates much of the burden.

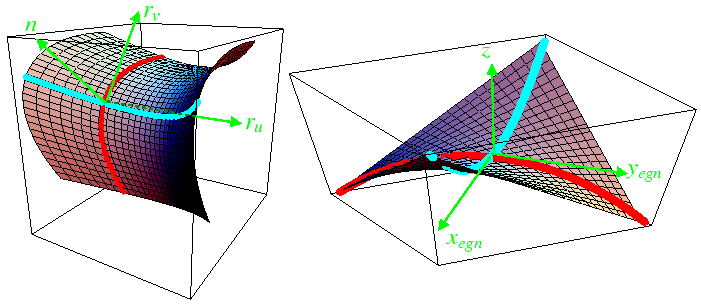

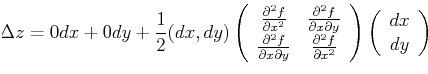

Most of the practical concepts derive from a second-order Taylor expansion of a surface near a point. The first-order terms define a tangent plane; the tangent plane determines the surface normal. The second-order terms in the Taylor expansion form a matrix and a quadratic form that can be used to formulate an expression for curvature. The eigenvalues of the second-order matrix are of fundamental importance.

The Taylor expansion about a particular point on the surface

takes a particularly simple form if the origin of the coordinate system

is located at the point and the ![]() -axis is taken along the surface normal

as illustrated in the following figure.

-axis is taken along the surface normal

as illustrated in the following figure.

|

|

In this coordinate system, the Taylor expansion of ![]() must be of the form

must be of the form

If this coordinate system is rotated about the

The method in the figure suggests a method to calculate the normals and curvatures for a surface. Those results are tabulated below.

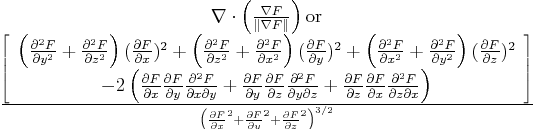

| Level Set Surfaces: Tangent Plane, Surface Normal, and Curvature |

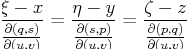

| Tangent Plane (

|

| Normal |

| Mean Curvature |

|

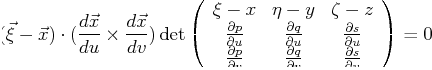

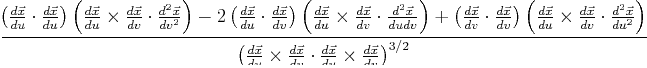

| Parametric Surfaces: Tangent Plane, Surface Normal, and Curvature |

| Tangent Plane (

|

|

| Normal |

|

| Mean Curvature |

|

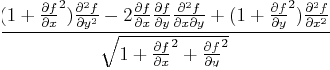

| Graph Surfaces: Tangent Plane, Surface Normal, and Curvature |

| Tangent Plane (

|

| Normal |

| Mean Curvature |

|