|

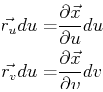

(15-2) |

|

(15-2) |

| (15-3) |

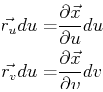

However, the operation of taking the norm in the definition of

the surface patch ![]() indicates that some information is getting

lost--this is the local normal orientation of the surface.

There are two choices for a normal (inward or outward).

indicates that some information is getting

lost--this is the local normal orientation of the surface.

There are two choices for a normal (inward or outward).

When calculating some quantity that does not have vector nature, only the magnitude of the function over the area matters (as in Eq. 15-4). However, when calculating a vector quantity, such as the flow through a surface, or the total force applied to a surface, the surface orientation matters and it makes sense to consider the surface patch as a vector quantity:

|

(15-5) |

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-15) |

| (html Lecture-15) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-15) |

| Integrals of Anisotropic Surface Energy

The surface energy of single crystals often depends on the

surface orientation.

This is especially the case for materials that have covalent

and/or ionic bonds.

To find the total surface energy of such a single crystal, one has to integrate an orientation-dependent surface energy over the surface of a body. This example compares the total energy of such an anisotropic surface energy integrated over a sphere and a cube that enclose the same volume.

|

The above calculation compares two fixed shapes--to find the surface which has the least energy for enclosing a given volume, one would employ a construction known as the Wulff Theorem.