Reappraise the simplest integration operation,

![]() .

Temporarily ignore all the tedious mechanical rules of finding and

integral and concentrate on what integration does.

.

Temporarily ignore all the tedious mechanical rules of finding and

integral and concentrate on what integration does.

Integration replaces a fairly complex process--adding up all

the contributions of a function ![]() --with a clever new function

--with a clever new function

![]() that only needs end-points to return the result of a complicated summation.

that only needs end-points to return the result of a complicated summation.

It is perhaps initially astonishing that this complex operation

on the interior of the integration domain can be incorporated merely by

the domain's endpoints.

However, careful reflection provides a counterpoint to this marvel.

How could it be otherwise?

The function ![]() is specified and there are no surprises lurking

along the

is specified and there are no surprises lurking

along the ![]() -axis that will trip up

-axis that will trip up ![]() as it marches merrily along between

the endpoints.

All the facts are laid out and they willingly submit to the process

their preordination by

as it marches merrily along between

the endpoints.

All the facts are laid out and they willingly submit to the process

their preordination by ![]() by virtue of the endpoints.1

by virtue of the endpoints.1

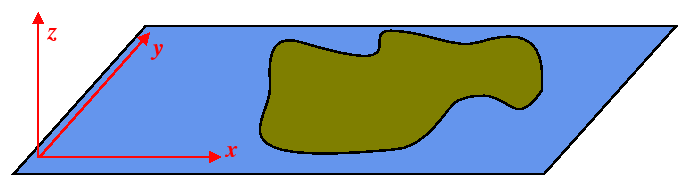

The idea naturally translates to higher dimensional integrals and these are the basis for Green's theorem in the plane, Stoke's theorem, and Gauss (divergence) theorem. Here is the idea:

|

|

The analog of the ``Fundamental Theorem of Differential and

Integral Calculus''2 for a region

![]() bounded in a plane with

normal

bounded in a plane with

normal ![]() that is bounded by a curve

that is bounded by a curve

![]() is:

is:

|

(15-1) |

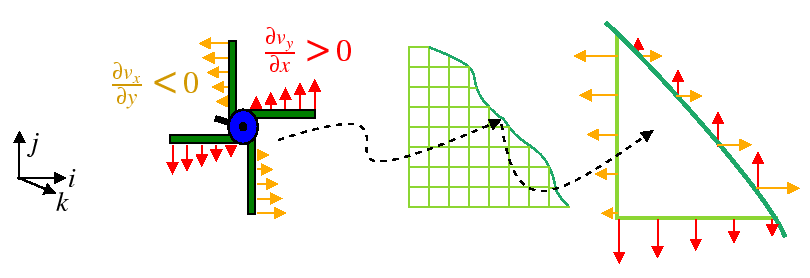

The following figure motivates Green's theorem in the plane:

|

|

The generalization of this idea to a surface

![]() bounding

a domain

bounding

a domain

![]() results in Stokes' theorem, which will be discussed

later.

results in Stokes' theorem, which will be discussed

later.

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-15) |

| (html Lecture-15) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-15) |

| Turing an integral over a domain into an integral over its boundary

Using Green's theorem in the plane to simplify the integration

to find the potential above a triangular path

that was evaluated in the last lecture.

Here we turn the two dimensional numerical integration which

requires

|