|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-12) |

| (html Lecture-12) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-12) |

| Curves, Tangents, Surfaces

|

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-12) |

| (html Lecture-12) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-12) |

| Curves, Tangents, Surfaces

|

Because the derivative of a curve with respect to its parameter is a tangent vector, the unit tangent can be defined immediately:

It is convenient to find a new parameter, ![]() , that

would make the denominator in Eq. 12-1 equal

to one.

This parameter,

, that

would make the denominator in Eq. 12-1 equal

to one.

This parameter, ![]() , is the arc-length:

, is the arc-length:

|

(12-3) |

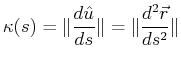

With the arc-length ![]() , the magnitude of the curvature is particularly

simple,

, the magnitude of the curvature is particularly

simple,

|

(12-4) |

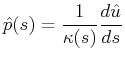

Furthermore, the rate at which the unit tangent changes direction is

a vector that must be normal to the tangent (because

![]() ) and therefore the unit normal

is defined by:

) and therefore the unit normal

is defined by:

|

(12-5) |

There two unit vectors that are locally normal

to the unit tangent vector

![]() and the curve unit normal

and the curve unit normal

![]() and

and

![]() .

This last choice is called the unit binormal,

.

This last choice is called the unit binormal,

![]() and the

three vectors together form a nice little moving orthogonal

axis pinned to the curve.

Furthermore, there are convenient relations between the vectors and differential

geometric quantities called the Frenet equations.

and the

three vectors together form a nice little moving orthogonal

axis pinned to the curve.

Furthermore, there are convenient relations between the vectors and differential

geometric quantities called the Frenet equations.

However, it should be pointed out that--although re-parameterizing a curve in terms of its arc-length makes for simple analysis of a curve--achieving this re-parameterization is not necessarily simple.

Consider the steps required to represent a curve

![]() in

terms of its arc-length:

in

terms of its arc-length:

If it does then we can perform the following operation:

These difficulties usually result in treating the problem symbolically and the resorting to numerical methods of achieving the integration and inversion steps.

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-12) |

| (html Lecture-12) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-12) |

| Calculating arclength

|