Next: Index

Up: Lecture_11_web

Previous: Vector Products

Next: Index

Up: Lecture_11_web

Previous: Vector Products

Subsections

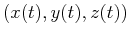

Consider a vector,  , as a point in space.

If that vector is a function of a real

continuous parameter for instance,

, as a point in space.

If that vector is a function of a real

continuous parameter for instance,  ,

then

,

then

represents the

loci as a function of a parameter.

represents the

loci as a function of a parameter.

If

is continuous, then it sweeps out

a continuous curve as

is continuous, then it sweeps out

a continuous curve as  changes continuously.

It is very natural to think of

changes continuously.

It is very natural to think of  as time and

as time and

as the trajectory of a particle--such a trajectory would

be continuous if the particle does not disappear at one

instant,

as the trajectory of a particle--such a trajectory would

be continuous if the particle does not disappear at one

instant,  , and reappear an instant later,

, and reappear an instant later,  ,

some finite distance distance away from

,

some finite distance distance away from

.

.

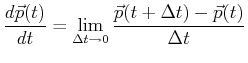

If

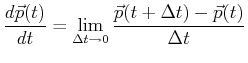

is continuous, then the limit:

is continuous, then the limit:

|

(11-5) |

Notice that the numerator inside the limit is a vector and

the denominator is a scalar;

so, the derivative is also a vector.

Think about the equation geometrically--it should be apparent

that the vector represented by the derivative is locally tangent

to the curve that is traced out by the points

,

,

, etc.

, etc.

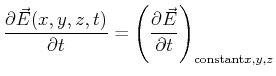

Review: Partial and total derivatives

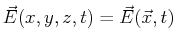

One might also consider a time- and space-dependent vector field, for

instance

could be the

force on a unit charge located at

could be the

force on a unit charge located at  at time

at time  .

.

Here, there are many different things which might be varied and

give rise to a derivative.

Such questions might be:

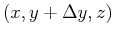

- How does the force on a unit charge differ for two nearby

unit-charge particles, say at

and at

and at

?

?

- How does the force on a unit charge located at

vary

with time?

vary

with time?

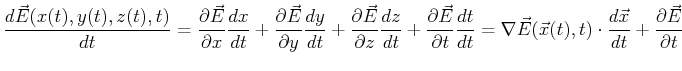

- How does the the force on a particle change as the

particle traverses some path

in space?

in space?

Each question has the ``flavor'' of a derivative, but each is

asking a different question.

So a different kind of derivative should exist for each type

of question.

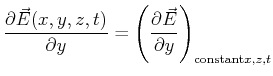

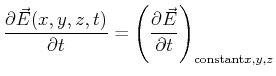

The first two questions are of the nature, ``How does a quantity

change if only one of its variables changes and the others are

held fixed?''

The kind of derivative that applies is the partial derivative.

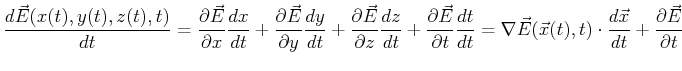

The last question is of the nature, ``How does a quantity change

when all of its variables depend on a single variable?''

The kind of derivative that applies is the total derivative.

The answers are:

-

|

(11-6) |

-

|

(11-7) |

-

|

(11-8) |

It is useful to think of vectors as spatial objects when

learning about them--but one shouldn't get stuck with the

idea that all vectors are points in two- or three-dimensional

space.

The spatial vectors serve as a good analogy to generalize

an idea.

For example,

consider the following chemical reaction:

| Reaction: |

H

|

O O

|

|

|

| Initial: |

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

| During Rx.: |

|

|

|

|

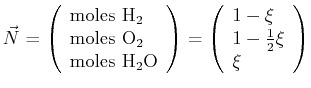

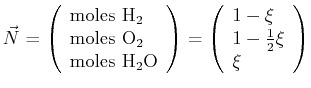

The composition could be written as a vector:

|

(11-9) |

and the variable  plays the role of the ``extent'' of the

reaction--so the composition variable

plays the role of the ``extent'' of the

reaction--so the composition variable  lives in

a reaction-extent (

lives in

a reaction-extent ( ) space of chemical species.

) space of chemical species.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![]() is continuous, then it sweeps out

a continuous curve as

is continuous, then it sweeps out

a continuous curve as ![]() changes continuously.

It is very natural to think of

changes continuously.

It is very natural to think of ![]() as time and

as time and

![]() as the trajectory of a particle--such a trajectory would

be continuous if the particle does not disappear at one

instant,

as the trajectory of a particle--such a trajectory would

be continuous if the particle does not disappear at one

instant, ![]() , and reappear an instant later,

, and reappear an instant later, ![]() ,

some finite distance distance away from

,

some finite distance distance away from

![]() .

.

![]() is continuous, then the limit:

is continuous, then the limit: