Next: Derivatives Vectors

Up: Lecture_11_web

Previous: Lecture_11_web

Next: Derivatives Vectors

Up: Lecture_11_web

Previous: Lecture_11_web

Subsections

The concept of vectors as abstract objects representing

a collection of data has already been presented.

Every student at this point has already encountered vectors

as representation of points, forces, and accelerations in

two and three dimensions.

MATHEMATICA Example

Example |

| (notebook Lecture-11) |

| (html Lecture-11) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-11) |

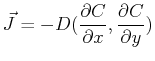

Solution to 2D Diffusion Equation for Point Source Initial Conditions

|

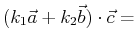

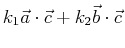

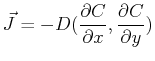

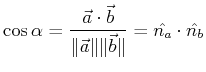

An inner (or dot-) project is multiplication of two vectors that

produces a scalar.

|

(11-1) |

The inner product is:

- linear, distributive

-

- symmetric

-

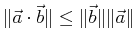

- satifies Schwarz inequality

-

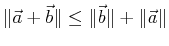

- satifies triangle inequality

-

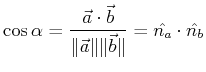

If

the vector components are in a cartesian (i.e., cubic lattice) space,

then there is a useful equation for the angle

between two vectors:

|

(11-2) |

where  is the unit vector that shares a direction with

is the unit vector that shares a direction with  .

Caution: when working with vectors in non-cubic crystal

lattices (e.g, tetragonal, hexagonal, etc.) the angle relationship above

does not hold.

One must convert to a cubic system first to calculate the angles.

.

Caution: when working with vectors in non-cubic crystal

lattices (e.g, tetragonal, hexagonal, etc.) the angle relationship above

does not hold.

One must convert to a cubic system first to calculate the angles.

The projection of a vector onto a direction  is a scalar:

is a scalar:

|

(11-3) |

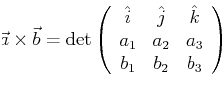

The vector product (or cross  ) differs from the dot (or inner) product

in that multiplication produces a vector from two vectors.

One might have quite a few choices about how to define

such a product, but the following idea proves to be

useful (and standard).

) differs from the dot (or inner) product

in that multiplication produces a vector from two vectors.

One might have quite a few choices about how to define

such a product, but the following idea proves to be

useful (and standard).

- normal

- Which way should the product vector point?

Because two vectors (usually) define a plane, the product

vector might as well point away from it.

The exception is when the two vectors are linearly dependent;

in this case the product vector will have zero magnitude.

The product vector is normal to the plane defined by

the two vectors that make up the product.

A plane has two normals, which normal should be picked?

By convention, the ``right-hand-rule'' defines which of

the two normal should be picked.

- magnitude

- Given that the product vector points away from the two

vectors that make up the product, what should be its

magnitude?

We already have a rule that gives us the cosine of the angle

between two vectors, a rule that gives the sine of the

angle between the two vectors would be useful.

Therefore, the cross product is defined so that its magnitude for two

unit vectors is the sine of the angle between them.

This has the extra utility that the cross product is zero when

two vectors are linearly-dependent (i.e., they do not define

a plane).

This also has the utility, discussed below, that the triple

product will be a scalar quantity equal to the volume

of the parallelepiped defined by three vectors.

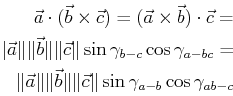

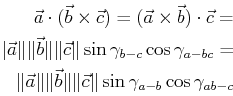

The triple product,

|

(11-4) |

where

is the angle between two vectors

is the angle between two vectors  and

and  and

and

is the angle between the vector

is the angle between the vector  and plane spanned by

and plane spanned by

and

and  .

is equal to the parallelepiped that has

.

is equal to the parallelepiped that has  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

emanating from its bottom-back corner.

,

emanating from its bottom-back corner.

If the triple product is zero, the volume between three vectors is

zero and therefore they must be linearly dependent.

© W. Craig Carter 2003-, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

![]() is a scalar:

is a scalar: