|

(19-1) |

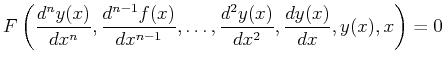

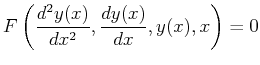

Ordinary differential equations are relations between a function of a single variable, its derivatives, and the variable:

|

(19-1) |

|

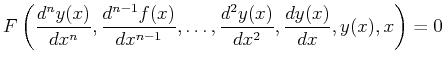

(19-2) |

|

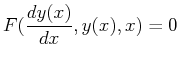

(19-3) |

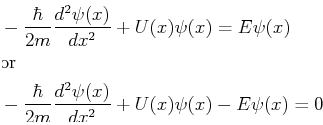

For example, the one-dimensional time-independent Shrödinger equation,

is a second-order ordinary differential equation that specifies a relation between the wave function,

Differential equations result from physical models of anything that varies--whether in space, in time, in value, in cost, in color, etc. For example, differential equations exist for modeling quantities such as: volume, pressure, temperature, density, composition, charge density, magnetization, fracture strength, dislocation density, chemical potential, ionic concentration, refractive index, entropy, stress, etc. That is, almost all models for physical quantities are formulated with a differential equation.

The following example illustrates how some first-order equations arise:

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-19) |

| (html Lecture-19) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-19) |

| Iteration: First-Order Sequences

Consider a function that changes according to its current size-that is, at a subsequent iteration, the function grows or shrinks according to how large it is currently.

which is equivalent to

|

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-19) |

| (html Lecture-19) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-19) |

| First-Order Finite Differences

The example above is not terribly useful because the change

at each increment is an integer and the function only has

values for integers.

To generalize, a forward difference can be added that

allows the variable of the function to ``go forward''

at an arbitrarily small increment,

If the rate of change of

or where |

|

MATHEMATICA |

| (notebook Lecture-19) |

| (html Lecture-19) |

| (xml+mathml Lecture-19) |

| First-Order Operators

The forward-difference equation considered above

relates the next iteration,

In this way, the

|